False Alerts:

Growing Evidence that Drug-Sniffing Dogs Reflect Police Bias

Jun 2011

Citation: Erowid E. "False Alerts: Growing Evidence that Drug-Sniffing Dogs Reflect Police Bias". Erowid Extracts. Jun 2011;20:6-7. Online edition: Erowid.org/freedom/police/police_article1.shtml

Police in Washington State now Training Dogs not to Alert on Cannabis

Update, August 2013: After Washington State passed a measure legalizing cannabis in November, 2012, the Washington State Patrol began training K9 dogs not to alert on cannabis. In a direct Tweet to Erowid, the Washington State Patrol (@wastatepatrol) clarified that "established dogs" are not being retrained "to avoid mj" because it "can't b done", but they are "simply not training our new dogs on that odor". See "WSP's new breed of drug-sniffing dog" - King5.com, Aug 12 2013

|

False Positives

A provocative research paper published in January 2011 showed that, rather than being neutral, police detection dogs alert where their handlers think they should. This research is one of only a handful of scientific attempts to test the validity of law enforcement claims of reliable detection.The study by Lit, Schweitzer, and Oberbauer caused a stir because, in their experiments to test detection dogs and their handlers, the researchers did not use any explosive or drug scents. Instead, they created a course inside a building and placed red paper markers on various objects to fool handlers into believing that marked locations contained scents and "Slim Jim" meat sticks as decoys to fool the dogs. Even with no legitimate targets present in the experiment, 85% of searches resulted in at least one alert by the handler-led detection dog. Only 21 out of the 144 police dog walk-throughs correctly reported no alerts by the dog, while 123 searches resulted in a combined total of 225 false alerts.

Even with no legitimate targets present in the experiment, 85% of searches resulted in at least one alert by the handler-led detection dog.

Lit et al. compared the results of their experiment to the "Clever Hans" effect. Clever Hans was a horse in the early 20th century who was said to know how to count, but was later confirmed to be reacting to subtle cues from his handler and the audience. Lit et al. write, "The 'Clever Hans' effect has become a widely accepted example not only of the involuntary nature of cues provided by onlookers [...], but of the ability of animals to recognize and respond to subtle cues provided by those around them. However, an additional important consideration was the willingness of onlookers to assign a biased interpretation of what they saw according to their expectations."1 Issues of influence, expectation, and human interpretation of animal behavior become extremely problematic when Clever Hans is providing legal evidence used by law enforcement. To complicate matters, an actual alert isn't even required as an unethical handler can simply report an alert that didn't happen.

Probable Cause with Four Legs

Also in January 2011, the Chicago Tribune examined data about law enforcement searches collected to study racial profiling issues. They found that only 44% of alerts during K9 inspections of automobiles resulted in the discovery of illegal drugs or paraphernalia, with hit rates much lower for Hispanic drivers. An Illinois State Representative and former prosecutor, Jim Durkin, calls police dogs "probable cause with four legs" and has tried and failed to pass legislation that would create a set of standards for training detection dogs. It's astonishing that there isn't one already.2

|

Extensive Australian Review

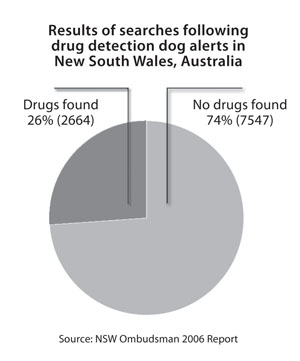

In 2001, a judge in Sydney, Australia ruled in Police v. Darby that the use of drug-sniffing dogs, without other probable cause to suspect an individual, was illegal. In response, the New South Wales (NSW) legislature passed a law allowing the general use of drug detection dogs and created an oversight role for an organization to track and review the use of the dogs. In 2006, the NSW Ombudsman issued an extensive report based on two years of data representing over 10,000 drug dog alerts.3 The review found that illegal drugs were found in only 26% of all searches that were initiated after a handler indicated that a dog alerted on the subject. The report softens the dismal performance by suggesting the false positives could be the result of "residual scents": after being searched and found not to possess any contraband, 60% of dog-alerted suspects "admitted to having had some contact with cannabis or to being at a place where cannabis was smoked."3 This unsubstantiated excuse for their deplorable success rate is offered by police despite their claim that dogs are "not trained to detect the odour of cannabis smoke". Improbably, some of the "residual scent" admissions collected by police were "related to drug use that was weeks, months and sometimes more than a year prior to the indication by the drug detection dog."3 Obviously this sort of remote past contact should not lead a detection dog to alert and establish probable cause for a search for current evidence.Disappointingly, the Ombudsman found that handlers rewarded dogs regardless of whether or not their alert was accurate, violating both common sense and the stated policy of NSW law enforcement dog handlers.3

Improbable Cause to Search

The fact that a drug dog alert constitutes probable cause to initiate a full search of a person or car should logically require that it is reasonable to assume a dog alert indicates that evidence of a crime is present. If the majority of alerts are for "residual" scents that are days, weeks, or months old, any presumption of reasonableness vanishes. Despite evidence to the contrary, the NSW Police Association states that dog alerts provide reasonable cause to search because they exclusively indicate the "carriage or recent use of drugs".3 Similarly, the primary U.S. Supreme Court cases upholding drug dog searches state that the canine sniff "discloses only the presence or absence of narcotics, a contraband item".4 But, as Justice Souter stated in his dissent of the defining case Illinois v. Caballes (2005), "[t]he infallible dog, however, is a creature of legal fiction [...] their supposed infallibility is belied by judicial opinions describing well-trained animals sniffing and alerting with less than perfect accuracy, whether owing to errors by their handlers, the limitations of the dogs themselves, or even the pervasive contamination of currency by cocaine."5It is important to distinguish between two distinct types of detection practices: in some cases dogs are set to roam free in an area and alert when they detect a target scent, but in most cases dogs accompany their handler and are assigned to sniff a specific person or vehicle. It is in this latter case that the Clever Hans effect is much more likely to appear. It remains unknown and untested whether police dogs themselves might carry biases, even when not attended by a handler, which could result in inappropriately high false positives on patchouli-scented hippies, jersey-sporting inner city youth, or glowstick-carrying ravers. After all, if a dog receives subtle cues over the years from its handler that certain characteristics are "suspicious", it is all too easy to assume that the dog could internalize those biases.

Change Afoot?

There are small indications that the winds of change might be blowing in U.S. courts. In September 2010, an appellate court in Texas overturned the murder conviction of a man who had been found guilty based on a curious "scent lineup" technique. Three years after the murder, police had three dogs sniff clothing worn by the victim when he was killed. The police investigator then took "scent swabs" from six individuals and placed them in separate coffee cans. The investigator stated under oath that the dogs alerted when they sniffed the coffee can containing a swab taken from the defendant. The appeals court found that "scent discrimination lineups, when used alone or as primary evidence, are legally insufficient to support a conviction."6 Unfortunately, the appeals court did not throw out this unverified technique entirely and only found it could not be the sole evidence against a defendant. It seems that, at present, any technique involving a dog and a police officer is presumed accurate, and interpretation is left exclusively to the discretion of handlers.The research by Lit and colleagues revealing that dogs alert where their handlers think they should, the extensive review of drug detection dogs in New South Wales, and the lack of counter evidence have begun to persuasively demonstrate that detection dogs and their handlers are not able to neutrally detect evidence of illegal activity. Instead, these detection teams are influenced by the problematic biases that make necessary the 4th Amendment in the United States and privacy protections in other countries. If the alert of a detection dog is going to be used as evidence allowing searches, double-blind type field techniques must be developed that are proven to remove handler bias.

References #

- Lit L, Schweitzer JB, Oberbauer AM. "Handler beliefs affect scent detection dog outcomes". Anim Cogn. May 2011; 14(3):387-94.

- Hinkel D, Mahr J. "Tribune analysis: Drug-sniffing dogs in traffic stops often wrong". Chicago Tribune. Jan 6, 2011.

- Australia. NSW Ombudsman. Review of the Police Powers (Drug Detection Dogs) Act 2001. NSW. Sep 14, 2006.

- United States v. Place. 462 U.S. 696 (1983).

- Illinois v. Caballes. 543 U.S. 405 (2005).

- Winfrey v. Texas. 323 S.W. 3d 875 (2010).