The First Sapo Experience Report

Aug 2016

Citation: Pinchera M. "The First Sapo Experience Report". Erowid Extracts. Aug 2016;29:18-21. Online edition: Erowid.org/animals/phyllomedusa/phyllomedusa_article4.shtml

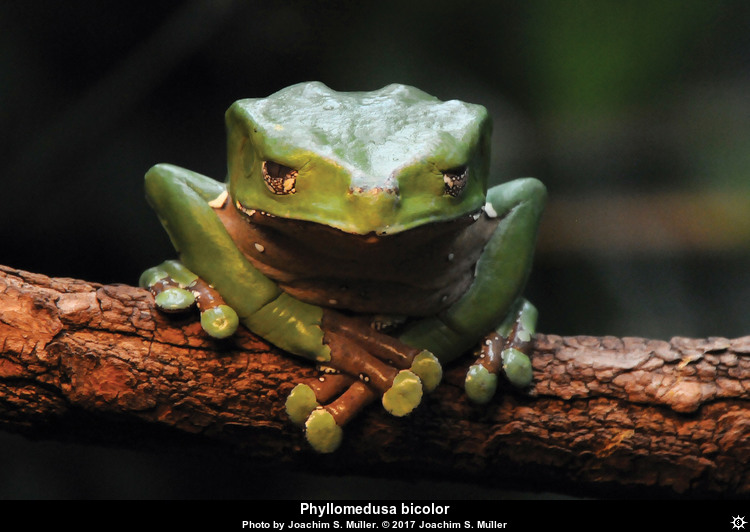

The 2015 book Sapo in My Soul: The Mats�s Frog Medicine is the unlikely story of how a curious former New York City chef authored the earliest-known, first-person experience report about the effects of Phyllomedusa bicolor secretions in humans, helping to bring global attention to a frog venom with unique medical and psychoactive properties.

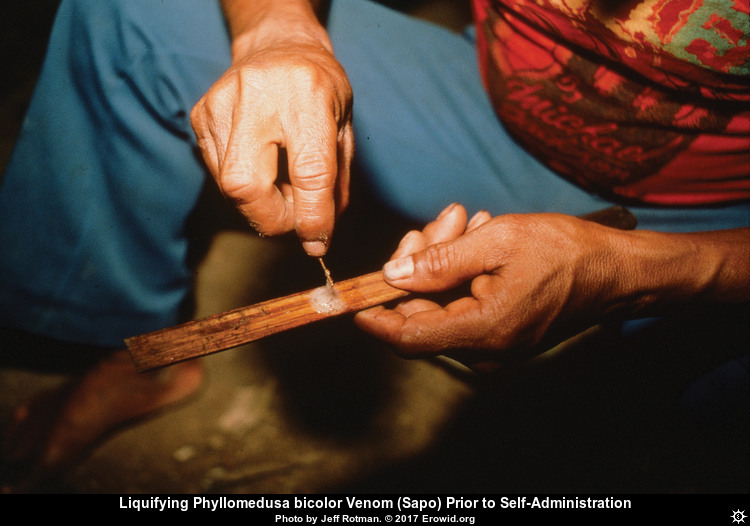

In mid-1986, investigative journalist Peter Gorman was pointing at objects in the home of Pablo, a Mats�s curandero (traditional healer) he'd just met, seeking to learn the tribe's words for various items. As Gorman motioned toward a small plastic bag hanging over a fire, Pablo excitedly pulled a stick from the bag--and spat on it.

"I had no idea what it was but I was not particularly afraid, because the night before we had done n�-n�, a [tobacco-based] snuff, and that hadn't hurt me", Gorman recalls. "And my guide Moises knew these guys and he didn't object, so I thought, 'Well, whatever he's doing is going to be interesting.'"

Pablo briskly mixed his saliva on the stick, forming a light paste, and then retrieved a twig from the fire.

"He grabbed my left arm--I couldn't pull it away--burned me twice, quickly scraped away the skin, and put the paste he made onto the exposed subcutaneous layers of flesh", Gorman says.

Moments after the paste--reconstituted secretions of the bright green Amazonian tree frog Phyllomedusa bicolor--was applied, Gorman was thrust into hell.

"In about 15 seconds, my heart began to beat faster, my pulse seemed like it was going faster, my blood seemed to rush, I got very warm", he says. "At 30 seconds, I was very uncomfortable. I was hot and this was really making me sweat. I turned to Moises and asked, 'All right, what is this?' In the jungle region, Moises knew everything."

Despite having in-depth, first-hand knowledge about the activities and traditions of countless tribes in the region, Moises knew nothing about the stick in Pablo's hand.

"Sapo, Petro, sapo", the curandero whispered, adding to the confusion.

"I had no idea what he was talking about--'sapo' means toad in Spanish", Gorman says. "Within five minutes, I started to convulse and throw up. I got down on my hands and knees because I couldn't stand anymore and I wanted the coolness of the clay against my forehead."

He collapsed on the ground.

"I felt my heart was going to explode; I thought my head was going to explode; I thought I was so hot my brain was certainly fried. It was a terrifying experience."

As he writhed in agony, 20 kids from the village started kicking him as though he was a dying animal, like, "Hey, is he dead yet? Can we put him on the spit or what?". Gorman described thinking "Oh my god, they just poisoned me, I'm dying, and they already want to put me on the goddamned fire. I've seen them put animals on the fire--they put animals on the fire while alive. I do NOT want to be put on the damn fire."

Gorman awoke in his hut alone and with no one nearby. But he could hear people speaking in a normal tone. Then he realized he was hearing two women who were 50-70 feet away.

"I thought, 'That's extraordinary! What the heck's going on here?' And I looked around and into the trees to my left and saw some small motion, but not at the edge of the trees. It was as if I was seeing through the trees and there was motion in the inside. I realized, 'Hey there goes a small band of monkeys', and I could hear them as well. This was not normal. And when I went to stretch, it seemed like all of my muscles responded. Not just a normal stretch, but as if they were 'RRRRRRR!' I felt like, 'Whoa, I'm hearing better, I'm seeing better, I'm a strong motherfucker!' It sort of blew me away--and I hadn't died and they hadn't put me on the fire."

The perceptual change wasn't like seeing another dimension on ayahuasca. But it reinforced his awareness that we are missing out on something--many things--if we don't take seriously indigenous people and their knowledge. At the time, Gorman had no idea that his description of the ordeal would be the world's first published sapo experience report. "That wasn't in my head at all ... I was just thrilled I had something to share", he says.

Earlier explorers had shared second- and third-hand tales of "kamb�", which is synonymous with "sapo"--the word used by the Mats�s for the P. bicolor frog, its protective secretions, as well as the acts of capturing and milking it (herein, "sapo" is used solely in reference to the animal's secretions)--but it seemed little more than a myth, another curious entry in the anthropological record, until Gorman let the frog out of the bag by sharing his account with researchers, scientists, and mass media worldwide.

"I had feedback from [a few] anthropologists who said they [tried sapo] and hated me because they were going to write about it when they retired", Gorman says. "But because they were anthropologists, they couldn't admit that they [got involved in the peoples they were researching]. And my feeling was, 'I'm glad you did it. But I didn't mean to be No. 1; I wasn't trying to steal your thunder.' My job as a journalist is to jump in the frickin' water." (None of those anthropologists shared with Gorman details of their experiences or described having taken sapo more than once.)

Back in New York, he shared his sapo experience with, among others, his contacts at the American Museum of Natural History, and approached the consumer publishing world.

Gorman returned to Peru several months later in 1986 on assignment for Penthouse to write about the Mats�s, a feature for which the magazine flew in noted photographer Jeff Rotman.

The full report (121 pages on language and names, photo opportunities encountered, and a list of artifacts collected for the museum) of this trip includes Gorman's second experience of using sapo: "While [Pablo] is gone I receive a single shot of sappo [sic] in my left forearm. They will give me no more as the women remember my bad reaction last time and are apparently afraid I might not return ... Why have I done this drug again? I thought I would die the first time and now am sure of it ... I was not nearly as removed as the first time, in all [likelihood] attributable to having done half the amount."1

Meanwhile, Penthouse prepared for its exclusive story from "The Real Life Indiana Jones"--that's how they teased it in the issue preceding its intended publication. At the last minute, the story was cut because, as Gorman later learned, publisher Bob Guccione expected a cannibal tale. Gorman admits he likely used the word "cannibalism" during his pitch to the magazine, either metaphorically or in the context of an anecdote he'd been told during an earlier visit to the Mats�s--a tale which, if true, would be an exception since the Mats�s do not generally have cannibalistic tendencies.

Yet, Gorman's sapo story would get out. The earliest-known publication of his sapo experience report came in August 1987, appearing simultaneously in two foreign editions of Penthouse ("Mein Trip Mit Dem J�ger Tumi", German; "Visioenen Van Een Jacht", Dutch). Australian Penthouse was quick to follow with "Into the Mystic" (Oct. 1987), the story's first English-language publication.

Dr. Vittorio Erspamer, a pharmacologist working with the FIDIA Research Institute for the Neurosciences at the University of Rome, had been investigating peptides in amphibian skins (including P. bicolor) for decades2--always believing they could be beneficial for medicine, but lacking literature sufficient to justify using the material on humans.

"So when I gave the museum my information about using sapo, I believe, but I can't swear, that someone in the museum, knowing [Erspamer's] interest, got that to him. Then he made contact through a third party saying, 'Whoa, whoa, whoa! You did this? You're alive? Can I have some?'"

In 1988, Gorman returned from Peru with P. bicolor secretions in the typical Mats�s form--collected and dried on a stick--and provided samples to Charles Myers, curator of the American Museum of Natural History's herpetology department, and Erspamer.

More than 50 years earlier, in 1937, Erspamer discovered a new amine, which he named "enteramine" (5-hydroxytryptamine, now known as "serotonin"). That contribution was significant in many ways, but especially so in relation to understanding essential functions of the human brain and how brain chemistry is affected by psychedelics. "If neuroscience can be said to have a beginning", wrote Dr. David Nichols in the spring 2013 MAPS Bulletin, "one could argue that it occurred in 1954, with the idea that the action of LSD might be related to its effects on the brain serotonin system".

Like all of the greatest scientists, Erspamer was ahead of his time."If anyone already had samples, it would have been Erspamer", Gorman says. "I do think he looked at P. bicolor [in earlier research], but that it didn't grab his attention as much as some of the others."

Those others, he believes, included Phyllomedusa sauvagii--which contains dermorphin, a peptide also found in sapo that has analgesic properties and is estimated to be 30-40 times as potent as morphine--and some Dendrobatidae species poison-dart frogs.

Months after receiving Gorman's sapo, Erspamer reported that it consisted of up to 7% peptides by weight: dozens of different peptides, at least seven of which are bioactive. "No other amphibian skin can compete with it", he wrote. With his interest growing, Erspamer arranged for a doctor he trusted to visit Gorman at his Manhattan apartment.

"The doctor did tests, I did sapo. He had me hooked up to an EKG and different things were strapped to me and he was talking to Erspamer [on the phone] at the same time. So Erspamer knew the tests were done and that I didn't just make this shit up."

As a result of Gorman's story, Erspamer had more to work with than just hypotheses about the effects of sapo's peptides. Erspamer asked Gorman for a detailed account of his sapo experience, which would become the basis of the first peer-reviewed report investigating whether the chemistry of P. bicolor secretions could explain the effects described.3

"And the answer was yes, they could explain every aspect except for the point at which it felt like a frog was moving through me in the throes of it all", Gorman says. "[Erspamer] believed those were hallucinations, maybe brought on by my use of n�-n� at a similar time. But the increased heart rate, the sweating, the feeling of strength, satiation, not being hungry, not being tired for a couple of days, all of that was explained by the peptides in the sapo, once he broke it down."

In the course of his research, Erspamer administered sapo to twelve end-stage cancer patients to see if there was any noticeable benefit, specifically whether two of the prominent peptides would eliminate their pain.

"If Erspamer himself wasn't dead, I wouldn't even mention this because I want no one to besmirch him", Gorman says. "But he knew what a dying cancer patient looked like--and these people were due to die that day--he admitted to me that this was their last chance."

Nine of the patients died within 24 hours of being given sapo and three patients lived pain free for a few more days before succumbing to cancer, Erspamer wrote to Gorman after the experiment.

Gorman is emotional when sharing what he hopes will come from his chance encounter with sapo and the subsequent scientific developments, having clearly thought about the matter for decades.

"My mother, with end-stage cancer, was on a morphine drip 24 hours a day; basically in a drug-induced coma. "Imagine if my mother had been allowed to experience her last month totally awake and without pain, to tell us the stories that she was saving for the last day... and if we could tell her what we wanted to tell her... What if she could have been walking around for those last 30 days, making food, washing floors, having a piece of cheese and a glass of wine in the backyard, aware, 'Yeah, you're dying now. Enjoy the sunset, motherfucker.' To me, that seems like such a gift."

Researchers have continued the search for medicine in sapo, its isolated peptides, and derivatives, including work being done by some of those who were around Erspamer and are now with pharmaceutical companies.

The bradykinin peptide found in sapo is among the most promising, as it appears to be able to piggyback other chemicals safely through the blood-brain barrier (BBB). Some drugs cannot cross this barrier. If the bradykinin peptide could reliably be used to deliver drugs through the BBB, it would be a valuable medical discovery. Researchers are looking at whether this could result in more effective treatment of Alzheimer's disease, brain cancer, and countless other ailments.

"Sapo might just be the very beginning of exploration", Gorman says. "There might be 1,000 amphibians out there with tons of material that can help us. But we needed to start somewhere, with somebody saying, 'I did this and I didn't die.'"

In mid-1986, investigative journalist Peter Gorman was pointing at objects in the home of Pablo, a Mats�s curandero (traditional healer) he'd just met, seeking to learn the tribe's words for various items. As Gorman motioned toward a small plastic bag hanging over a fire, Pablo excitedly pulled a stick from the bag--and spat on it.

"I had no idea what it was but I was not particularly afraid, because the night before we had done n�-n�, a [tobacco-based] snuff, and that hadn't hurt me", Gorman recalls. "And my guide Moises knew these guys and he didn't object, so I thought, 'Well, whatever he's doing is going to be interesting.'"

Pablo briskly mixed his saliva on the stick, forming a light paste, and then retrieved a twig from the fire.

"He grabbed my left arm--I couldn't pull it away--burned me twice, quickly scraped away the skin, and put the paste he made onto the exposed subcutaneous layers of flesh", Gorman says.

Moments after the paste--reconstituted secretions of the bright green Amazonian tree frog Phyllomedusa bicolor--was applied, Gorman was thrust into hell.

"In about 15 seconds, my heart began to beat faster, my pulse seemed like it was going faster, my blood seemed to rush, I got very warm", he says. "At 30 seconds, I was very uncomfortable. I was hot and this was really making me sweat. I turned to Moises and asked, 'All right, what is this?' In the jungle region, Moises knew everything."

Despite having in-depth, first-hand knowledge about the activities and traditions of countless tribes in the region, Moises knew nothing about the stick in Pablo's hand.

"Sapo, Petro, sapo", the curandero whispered, adding to the confusion.

"I had no idea what he was talking about--'sapo' means toad in Spanish", Gorman says. "Within five minutes, I started to convulse and throw up. I got down on my hands and knees because I couldn't stand anymore and I wanted the coolness of the clay against my forehead."

He collapsed on the ground.

"I felt my heart was going to explode; I thought my head was going to explode; I thought I was so hot my brain was certainly fried. It was a terrifying experience."

As he writhed in agony, 20 kids from the village started kicking him as though he was a dying animal, like, "Hey, is he dead yet? Can we put him on the spit or what?". Gorman described thinking "Oh my god, they just poisoned me, I'm dying, and they already want to put me on the goddamned fire. I've seen them put animals on the fire--they put animals on the fire while alive. I do NOT want to be put on the damn fire."

Gorman awoke in his hut alone and with no one nearby. But he could hear people speaking in a normal tone. Then he realized he was hearing two women who were 50-70 feet away.

"I thought, 'That's extraordinary! What the heck's going on here?' And I looked around and into the trees to my left and saw some small motion, but not at the edge of the trees. It was as if I was seeing through the trees and there was motion in the inside. I realized, 'Hey there goes a small band of monkeys', and I could hear them as well. This was not normal. And when I went to stretch, it seemed like all of my muscles responded. Not just a normal stretch, but as if they were 'RRRRRRR!' I felt like, 'Whoa, I'm hearing better, I'm seeing better, I'm a strong motherfucker!' It sort of blew me away--and I hadn't died and they hadn't put me on the fire."

The perceptual change wasn't like seeing another dimension on ayahuasca. But it reinforced his awareness that we are missing out on something--many things--if we don't take seriously indigenous people and their knowledge. At the time, Gorman had no idea that his description of the ordeal would be the world's first published sapo experience report. "That wasn't in my head at all ... I was just thrilled I had something to share", he says.

Earlier explorers had shared second- and third-hand tales of "kamb�", which is synonymous with "sapo"--the word used by the Mats�s for the P. bicolor frog, its protective secretions, as well as the acts of capturing and milking it (herein, "sapo" is used solely in reference to the animal's secretions)--but it seemed little more than a myth, another curious entry in the anthropological record, until Gorman let the frog out of the bag by sharing his account with researchers, scientists, and mass media worldwide.

"I had feedback from [a few] anthropologists who said they [tried sapo] and hated me because they were going to write about it when they retired", Gorman says. "But because they were anthropologists, they couldn't admit that they [got involved in the peoples they were researching]. And my feeling was, 'I'm glad you did it. But I didn't mean to be No. 1; I wasn't trying to steal your thunder.' My job as a journalist is to jump in the frickin' water." (None of those anthropologists shared with Gorman details of their experiences or described having taken sapo more than once.)

"Why have I done this drug again? I thought I would die the first time..."

Gorman returned to Peru several months later in 1986 on assignment for Penthouse to write about the Mats�s, a feature for which the magazine flew in noted photographer Jeff Rotman.

The full report (121 pages on language and names, photo opportunities encountered, and a list of artifacts collected for the museum) of this trip includes Gorman's second experience of using sapo: "While [Pablo] is gone I receive a single shot of sappo [sic] in my left forearm. They will give me no more as the women remember my bad reaction last time and are apparently afraid I might not return ... Why have I done this drug again? I thought I would die the first time and now am sure of it ... I was not nearly as removed as the first time, in all [likelihood] attributable to having done half the amount."1

Meanwhile, Penthouse prepared for its exclusive story from "The Real Life Indiana Jones"--that's how they teased it in the issue preceding its intended publication. At the last minute, the story was cut because, as Gorman later learned, publisher Bob Guccione expected a cannibal tale. Gorman admits he likely used the word "cannibalism" during his pitch to the magazine, either metaphorically or in the context of an anecdote he'd been told during an earlier visit to the Mats�s--a tale which, if true, would be an exception since the Mats�s do not generally have cannibalistic tendencies.

Yet, Gorman's sapo story would get out. The earliest-known publication of his sapo experience report came in August 1987, appearing simultaneously in two foreign editions of Penthouse ("Mein Trip Mit Dem J�ger Tumi", German; "Visioenen Van Een Jacht", Dutch). Australian Penthouse was quick to follow with "Into the Mystic" (Oct. 1987), the story's first English-language publication.

Enter the Scientist

"The American Museum of Natural History would take reports like mine, from what I understand, and disseminate them to people who were interested in that field", Gorman says.Dr. Vittorio Erspamer, a pharmacologist working with the FIDIA Research Institute for the Neurosciences at the University of Rome, had been investigating peptides in amphibian skins (including P. bicolor) for decades2--always believing they could be beneficial for medicine, but lacking literature sufficient to justify using the material on humans.

"So when I gave the museum my information about using sapo, I believe, but I can't swear, that someone in the museum, knowing [Erspamer's] interest, got that to him. Then he made contact through a third party saying, 'Whoa, whoa, whoa! You did this? You're alive? Can I have some?'"

In 1988, Gorman returned from Peru with P. bicolor secretions in the typical Mats�s form--collected and dried on a stick--and provided samples to Charles Myers, curator of the American Museum of Natural History's herpetology department, and Erspamer.

The earliest-known publication of Gorman's sapo experience report came in August 1987...

Like all of the greatest scientists, Erspamer was ahead of his time."If anyone already had samples, it would have been Erspamer", Gorman says. "I do think he looked at P. bicolor [in earlier research], but that it didn't grab his attention as much as some of the others."

Those others, he believes, included Phyllomedusa sauvagii--which contains dermorphin, a peptide also found in sapo that has analgesic properties and is estimated to be 30-40 times as potent as morphine--and some Dendrobatidae species poison-dart frogs.

Months after receiving Gorman's sapo, Erspamer reported that it consisted of up to 7% peptides by weight: dozens of different peptides, at least seven of which are bioactive. "No other amphibian skin can compete with it", he wrote. With his interest growing, Erspamer arranged for a doctor he trusted to visit Gorman at his Manhattan apartment.

"The doctor did tests, I did sapo. He had me hooked up to an EKG and different things were strapped to me and he was talking to Erspamer [on the phone] at the same time. So Erspamer knew the tests were done and that I didn't just make this shit up."

As a result of Gorman's story, Erspamer had more to work with than just hypotheses about the effects of sapo's peptides. Erspamer asked Gorman for a detailed account of his sapo experience, which would become the basis of the first peer-reviewed report investigating whether the chemistry of P. bicolor secretions could explain the effects described.3

"And the answer was yes, they could explain every aspect except for the point at which it felt like a frog was moving through me in the throes of it all", Gorman says. "[Erspamer] believed those were hallucinations, maybe brought on by my use of n�-n� at a similar time. But the increased heart rate, the sweating, the feeling of strength, satiation, not being hungry, not being tired for a couple of days, all of that was explained by the peptides in the sapo, once he broke it down."

In the course of his research, Erspamer administered sapo to twelve end-stage cancer patients to see if there was any noticeable benefit, specifically whether two of the prominent peptides would eliminate their pain.

"If Erspamer himself wasn't dead, I wouldn't even mention this because I want no one to besmirch him", Gorman says. "But he knew what a dying cancer patient looked like--and these people were due to die that day--he admitted to me that this was their last chance."

Nine of the patients died within 24 hours of being given sapo and three patients lived pain free for a few more days before succumbing to cancer, Erspamer wrote to Gorman after the experiment.

Gorman is emotional when sharing what he hopes will come from his chance encounter with sapo and the subsequent scientific developments, having clearly thought about the matter for decades.

"My mother, with end-stage cancer, was on a morphine drip 24 hours a day; basically in a drug-induced coma. "Imagine if my mother had been allowed to experience her last month totally awake and without pain, to tell us the stories that she was saving for the last day... and if we could tell her what we wanted to tell her... What if she could have been walking around for those last 30 days, making food, washing floors, having a piece of cheese and a glass of wine in the backyard, aware, 'Yeah, you're dying now. Enjoy the sunset, motherfucker.' To me, that seems like such a gift."

Researchers have continued the search for medicine in sapo, its isolated peptides, and derivatives, including work being done by some of those who were around Erspamer and are now with pharmaceutical companies.

The bradykinin peptide found in sapo is among the most promising, as it appears to be able to piggyback other chemicals safely through the blood-brain barrier (BBB). Some drugs cannot cross this barrier. If the bradykinin peptide could reliably be used to deliver drugs through the BBB, it would be a valuable medical discovery. Researchers are looking at whether this could result in more effective treatment of Alzheimer's disease, brain cancer, and countless other ailments.

"Sapo might just be the very beginning of exploration", Gorman says. "There might be 1,000 amphibians out there with tons of material that can help us. But we needed to start somewhere, with somebody saying, 'I did this and I didn't die.'"

References #

- Gorman P. "Galvez River Expedition". Unpublished field report. 1986.

- Erspamer V, Melchiorri P, et al. "Phyllomedusa skin: a huge factory and store-house of a variety of active peptides". Peptides. 1985;6(Suppl 3):7-12.

- Erspamer V, Erspamer GF, et al. "Pharmacologocial Studies of Sapo from the Frog Phyllomedusa bicolor Skin: A Drug Used by the Peruvian Mats�s Indians in Shamanic Hunting Practices". Toxicon. Sept 1993;31(9):1099-111.

Photo Credits #